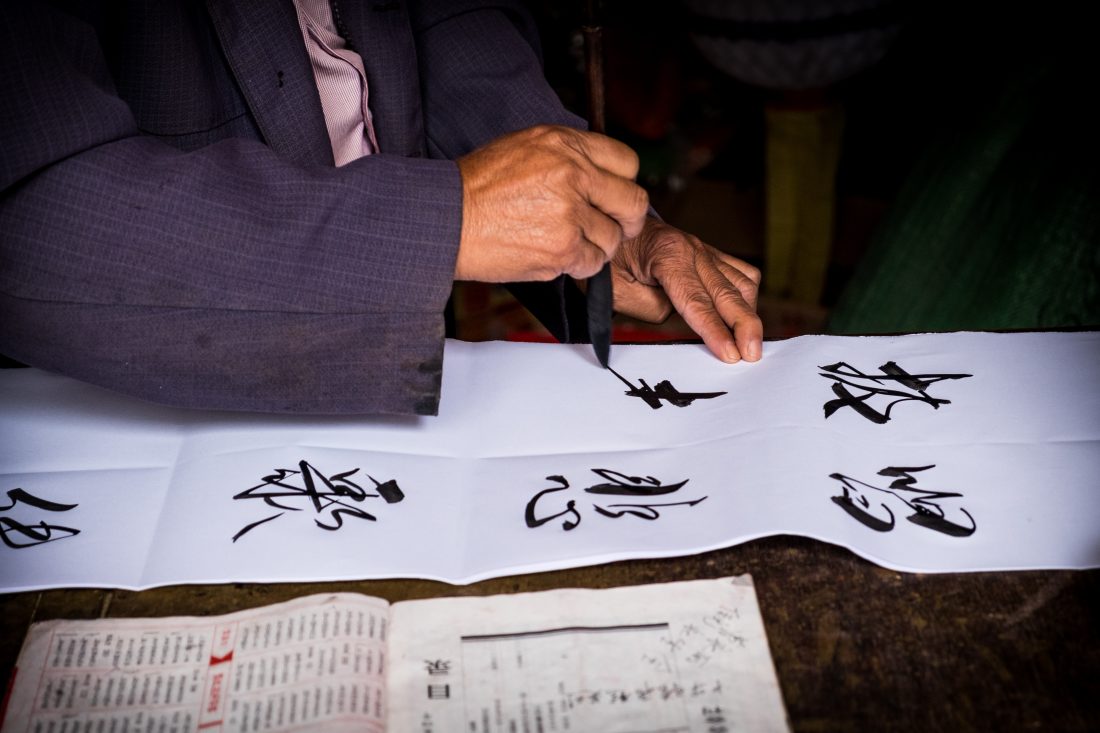

Once you start to learn Chinese you’ll soon come across chengyu 成语 or Chinese idioms. These are mainly four-character phrases that in most cases derive from ancient Chinese literature such as myths, legends, and historical stories. They are similar in some ways to Western proverbs, the ones that have their roots in Aesop’s fables or stories from Greek mythology. There are literally thousands of these Chinese idioms (30,000 according to one count), although many are no longer widely used. They are most commonly found in Chinese writing, although many also crop up in Chinese conversation.

With so many chengyu, which are the best ones to learn? And if you are a teacher, which chengyu should you introduce to your students? Although it’s tempting to learn the chengyu that have the most interesting stories behind them, those with the best “back stories” tend to be the ones that are rarely used. So it’s probably best to focus on idioms that are most often used in everyday life, even if they can be a bit prosaic. Here are some of the most useful and easy-to-use idioms in Chinese:

Chengyu / Chinese idioms for everyday life

显而易见 — (Xiǎn’ér yì jiàn)

This high-usage Chinese expression means “obvious” or “clear to see”. The phrase implies that the truth is readily apparent if you have a clear mind and an unbiased perspective. Although you may not hear it often in everyday conversation, you will certainly come across it in debates, formal presentations, essays, and written arguments.

众所周知 — (Zhòng suǒ zhōu zhī)

Another high-frequency chengyu meaning “it is well-known that…” or “everybody knows that…”. It is a favourite rhetorical device of high school students when introducing arguments in essays. It can also sometimes have a negative connotation, as in something being self-explanatory.

前所未有 — (Qián suǒ wèi yǒu)

This idiom meaning ‘unprecedented’ or “never happened before” is also relatively high-frequency – it regularly appears on lists of Top 10 Commonly Used Chengyu in News broadcasts. It comes from a poem by Tang Dynasty writer Du Fu where he describes the unprecedented severity of a snowstorm.

不可思议 — (Bù kě sī yì)

This Chinese idiom was originally a Buddhist term describing those mysteries of the universe that can’t be explained. So it means “unbelievable” or “inconceivable”.

千方百计 — (Qiān fang bǎi jì)

The meaning of this Chinese idiom is literally “a thousand ways, a hundred plans”, and so it means “to do everything possible”. This is one of the chengyu you might come across on an HSK word list. It is believed to originate from a Confucian encyclopedia in which the scholar, Zhu Xi, discusses the ways to catch a thief.

先发制人 — (Xiān fā zhì rén)

先发制人 is a frequently used Chinese idiom that translates to “pre-emptive strike” or “take the initiative to subdue the enemy”. Its literal meaning is something like “first attack the people…”, and it derives from a historical event at the end of the Qin Dynasty. Like many chengyu, there’s a long and intricate story behind it. In summary, during a period of rebellions throughout the country, three rebel leaders convened to discuss their next move. Two of the leaders recognized that the third was weak and hesitant, so they made a bold move: before he could say a word, they swiftly cut off his head and took charge of the rebellion.

Initially, this Chinese expression was used to talk about military strategy but now can be used in other situations such as sport and business.

乱七八糟 — (Luàn qī bā zāo)

This relatively common saying is used to describe something disorganised and messy. On first reading, the literal meaning “chaotic seven, eight bad” makes no sense at all. However, it is based on two actual historical events. The “chaotic seven” refers to the chaotic period in Chinese history when seven kingdoms revolted against the Han Dynasty in 154BC. The “eight bad” refers to another rebellion five hundred years later, in which eight would-be kings contended for the vacant emperor’s throne in what came to be known as the Eight Kings Rebellion.

脱颖而出 — (Tuō yǐng’ér chū)

The meaning of this expression is “talent or skill comes to the fore”. It comes from an old story from the Warring States period. The chengyu is comparing a capable person to an awl in a cloth bag (an awl is a sharp pointed tool for making holes in leather and other fabrics). Even though it is inside the bag, everyone can see the sharp point sticking out – like talent, it is hard to keep hidden.

一见钟情— (Yī jiàn zhōng qíng)

This Chinese idiom translates into “love at first sight” and is mostly used to describe romantic love between two people. However, you could also use it to describe a thing you love the first time you see it.

一心一意 — (Yī xīn yī yì)

Literally, this means “one heart, one mind”. It can be used in a variety of contexts but most commonly in a romantic sense. For example, you could use this Chinese expression if you wanted to say that you loved someone with all your heart.

三心二意 — (Sān xīn èr yì)

Still on the subject of love and romance, this is another idiom used for matters of the heart. However it is almost the antonym of 一心一意; it means “three hearts, two minds” or, in other words, to be unfocused and not know what you want. So in matters of the heart and romance, it implies that you aren’t really committed to the relationship.

马马虎虎 — (Mǎmǎ hǔhǔ)

This Chinese idiom is a popular one for foreigners to learn because it is so simple to remember (literally “horse horse tiger tiger”). It can sound a bit old-fashioned, more likely to be used by the older generation. Its main meaning is “careless” or “sloppy” but is now also used to mean “so-so” or “passable”.

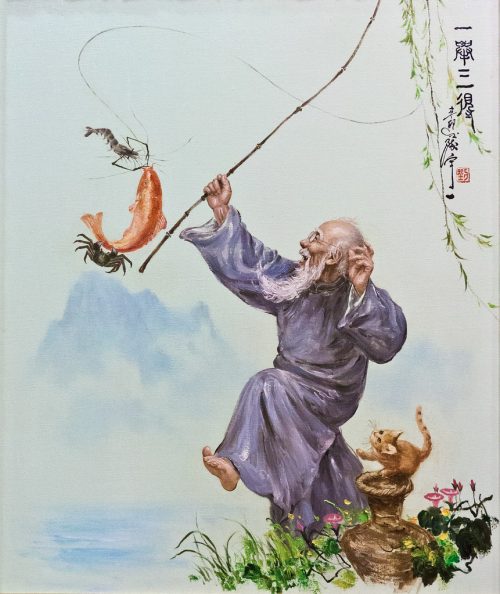

一举两得— (Yī jǔ liǎng dé)

We all know the saying in English “to kill two birds with one stone”, that is do one thing but get two benefits, and this Chinese expression is very similar in meaning. The literal translation is “one act two gains”. This idiom comes from a story about a village that was being terrorised by two tigers killing all their cattle. One of the smarter villagers came up with a plan of action: wait until the two tigers fight each other. The stronger tiger will kill the weaker one, but most probably will be injured in the process, making it easier for the villagers to finish it off.

Plus another four Chinese idioms that are relatively common in everyday Chinese:

出人意料 — (Chū rén yì liào)

This Chinese idiom means “unexpected” or literally “beyond people’s expectations”.

独一无二— (Dú yī wú’èr)

The meaning of this idiom is “unique and unmatched”, “unrivalled”.

忠言逆耳— (Zhōng yán nì’ěr)

This has the meaning of “faithful words offend the ear”, in other words: the truth hurts.

理所当然 — (Lǐ suǒ dāng rán)

A not uncommon chengyu, it means “as it should be” or “naturally”.

Chengyu / Chinese idioms for work

雄心勃勃 — (Xióng xīn bóbó)

Some of the most common Chinese idioms are those that describe personality types. 雄心勃勃 means “ambitious” (literally “mighty heart and exuberant”). Although in English ‘ambitious’ can sometimes have a negative meaning, this Chinese idiom generally has a positive connotation.

能者多劳 — (Néng zhě duō láo)

Here’s a handy saying for work: “capable people should do more of the work”. You can use this when delegating a task you don’t want to do because you’re flattering the person while fobbing off the work to them!

埋头苦干— (Mái tóu kǔ gàn)

This idiom is used to describe working hard and with deep concentration and means “to bury oneself in work” or “up to one’s neck in work”. (It literally means “head down, working hard”).

废寝忘食 — (Fèi qǐn wàng shí)

Another idiom to describe “hard-working”, this chengyu literally means “fail to sleep, forget to eat”, or one is working so hard they have no time to eat and sleep.

胸有成竹 — (Xiōng yǒu chéng zhú)

This chengyu has the meaning of gaining confidence by being well-prepared for something, and by having a well-thought-out plan in mind. It comes from the story of the painter who observed bamboo for many years, at all times of the day, in all seasons and types of weather, so he was then able to paint a bamboo scene without draft sketches.

一丝不苟 — (Yī sī bù gǒu)

This can be a good quality to have in the workplace because it means being meticulous in your work and paying attention to details.

半途而废 — (Bàn tú’ér fèi)

Hopefully, you won’t need this Chinese idiom to talk about your work because its literal translation is “halfway but fail”, or “to give up when the job is only half done”. It comes from the story of a man who had a tendency to begin things but would give up halfway. At one point, his wife encouraged him to pursue his studies, but as soon as he encountered difficulties, he naturally abandoned them and came back home. In response, his wife cut in half the silk material she had been weaving, explaining that just as she had wasted her time making the cloth by cutting it in two, he had also wasted his time by not completing his studies.

Chengyu / Chinese idioms that will impress your Chinese friends

卧虎藏龙 — (Wò hǔ cáng lóng)

Everyone knows the Chinese movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. But did you know the title actually comes from a Chinese idiom? It is from a Northern Zhou dynasty poem and has come to be used to describe people or things with hidden talents, waiting to be discovered.

入乡随俗— (Rù xiāng suí sú)

The literal meaning of this chengyu is “when you enter another region, follow the customs there”, or as we would say in English “when in Rome do as the Romans do”. In the original story, two merchant brothers travelled to a remote town where the local customs were backward and unrefined. One of the brothers accepted the principle of doing as the Romans do and adopted their customs. As a result, the town welcomed him and ended up buying his wares at a high price. But the other brother refused to act like the locals, angering them and they ended up driving him out of the town.

一路平安 — (Yī lù píng’ān)

This chengyu is a way to wish people a safe journey, particularly if they are travelling some distance. It literally means “journey safe and peaceful”. It is a little more sophisticated than other bon voyage expressions (like 旅途愉快) because it is a quote from a Ming Dynasty poet, Fan Yiyi.

掘墓鞭尸 — (Jué mù biān shī)

This Chinese idiom is a bit macabre because it translates as “digging up graves and whipping corpses”! It comes from an incident from the Warring States Period of Chinese history. The king had exiled one of his generals while also having the general’s father and brother put to death. When the king died, the vengeful general returned to his home kingdom, dug up the king’s grave, and had him whipped 300 times. (He also stamped on the corpse multiple times for good measure). Naturally, it is used to describe a deep hatred or a sadistic nature.

熟能生巧 — (Shú néng shēng qiǎo)

Let’s finish with a Chinese idiom that can be used to keep you motivated while you learn Chinese. This chengyu is from a tale about an archer who was displaying his skills in front of a crowd of admirers. Everyone applauded his skill except for one old man who wasn’t impressed. The archer, annoyed, asked the old man what he could do that was special. The old man placed a bottle on the ground, then put a coin with a hole in the centre on the mouth of the bottle. He then lifted his arm and from a height poured oil through the hole in the coin and into the bottle, without spilling a drop. The amazed crowd asked how he did it, and he replied “I practised a lot”. This chengyu can be translated as “practice makes perfect”.

Should you learn/teach Chengyu?

Of course, it’s possible to speak Chinese well without knowing any Chinese idioms, just as someone can learn English to a high level without learning a single proverb. However, if your aim is to read newspapers, essays, and novels, then you are going to encounter Chinese idioms. And because many are a kind of shorthand that don’t make immediate sense, it will create some difficulties for you in fully understanding the text. In addition, chengyu are such a rich and treasured part of the Chinese language and culture, and if you want to fully immerse yourself in Chinese then you should become familiar with at least a few Chinese idioms.

A suggested approach is to learn some of the high-frequency Chinese idioms, such as the ones listed here. Keep your eye and ear out for idioms that keep cropping up in your reading and listening material. And if you are interested in the stories behind some of the chengyu – many of them are clever and/or amusing and reveal a lot about Chinese culture – there are lots of books, articles, YouTube videos, and other resources that provide explanations.

For teachers, the same advice applies: focus on teaching the most commonly used Chinese idioms first. Make sure you provide plenty of example sentences as well so that students know the context to use the chengyu. Many Chinese idioms have very precise meanings, and it is easy for Mandarin learners to use them incorrectly. For a bit of variety, introduce your students to a handful of chengyu that have interesting stories behind them – without expecting your students to memorise them. Above all, avoid the approach used in Chinese primary and secondary schools of providing long lists of idioms to learn by heart. For ninety percent of non-native speakers, this method will only produce boredom and frustration.

Don’t forget The Chairman’s Blog has several other articles offering useful advice for both teachers and students. For teachers:

Top 8 Ways Teachers Can Use ChatGPT to Create Lesson Plans

K-12 Schools Chinese Teaching Resources to Teach Mandarin

And for students here are a couple of recent blog posts of interest:

10 of the Best Chinese Graded Readers and Where to Find Them

10 Best Resources to Learn Chinese Through News

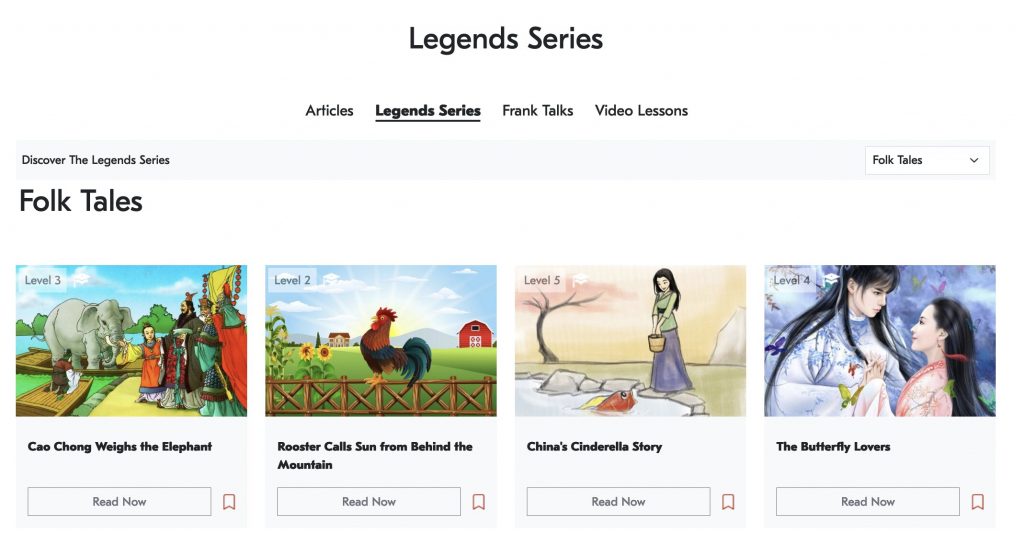

And if learning about Chinese idioms has piqued your interest in old Chinese stories, The Chairman’s Bao has a whole section of Chinese folk tales adapted to different levels that you can explore.

Author

Nick Dennis

Nick is an English teacher who has taught English as a Foreign Language in China, Italy and France. He has a Bachelor of Arts (Modern Languages), majoring in French, from the University of New South Wales. He loves travel, reading and football and, of course, learning languages. Four years ago, Nick and his wife co-founded an online English language school targeted at the Chinese market (since sold to Chinese investors). He has also ghost-written the autobiography of a well-known Australian horse trainer.