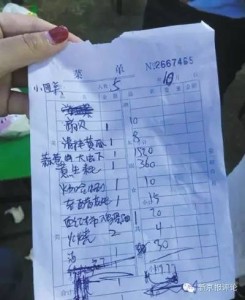

Authorities in the eastern Chinese city of Qingdao have been left red faced this week after a prawn debacle hit national headlines and once again showed the power of social media in China. The ’38 yuan large prawn’ scandal (38元大虾事件) occurred after a diner ordered a dish of prawns that was marked as costing 38 yuan, only to be given a bill for 1,520 yuan. The restaurant owner told the customer that the price was per prawn, before pulling out a stick and threatening to beat him up. It doesn’t matter how much famous local beer you have to wash it down, service like that is still going to leave a bad taste in your mouth.

The customer, Mr Zhu, who was on holiday with his family from Nanjing, called the police twice to the scene. The first time offers told him that there was nothing that they could do as it was a ‘price dispute’, which needs to be handled by the local trade and industry bureau – which at the time was shut. The next time they were called Mr Zhu was advised to pay the money to the restaurant owner, who justified the cost of the dish by stating that the prawns were freshly caught.

Mr Zhu, understandably disgruntled, decided to take to microblogging website Weibo to complain and the story immediately went viral. The timing of the dispute undoubtedly contributed to the public outrage as it came at the end of ‘Golden Week’, a national public holiday in China. Many people use the holiday as an opportunity to travel, where they are often forced to content with inflated prices and opportunist business owners, who prey on the heavy pockets of visiting tourists. As Qingdao is a popular tourist destination, it seems that the stage was set for the perfect (if not a little fishy) restaurant scam… that is, until social media struck back once again.

The story reminded me of a time three years ago I visited Qingdao with a friend who lived there. We had just been to the Tsingtao Beer Museum and sat at a nearby restaurant to enjoy the local fresh clams. We washed down the meal with a jug of beer before being told that the price was 800 yuan (bearing in mind a jug of beer in Qingdao usually costs 10 yuan). The owner threatened us that if we didn’t pay he would call the police.

After living in China for so long, it came as a big shock to be scammed so blatantly, especially after conversing with the restaurant owners in Chinese about our trip and the local area. We left a price that we knew was overly fair for the food and drink we had ordered and left, with the owner trying to pull us back – there was no chance we were waiting around for the police. If China wants to continue to attract tourists, it needs to start cracking down harder on petty scams such as these.

The owner of the seafood restaurant in the prawn scandal has since been fined 90,000 yuan, and the restaurant has closed down. Speaking to the BBC, Chinese sociologist Ding Xueliang commented that the story illustrated how “people, for many years, have accumulated so much distrust of consumer rights in China”. Netizens commented that in many places the phrase ‘有困难找警察’ (if there is trouble, call the police) has become ‘找警察有困难’ (there is trouble if the police are called).

In recent years China has increased penalties for fraud and false advertising. Each year on World Consumer Rights Day (15 March), CCTV issues a name-and-shame TV show on fraudulent companies.

Whilst this story highlights that there is still a lot that needs to be done to improve consumer rights in China, nobody can deny the public power of social media in tackling the issue.

As for me, I’ll be stick to my 炒蛋饭!