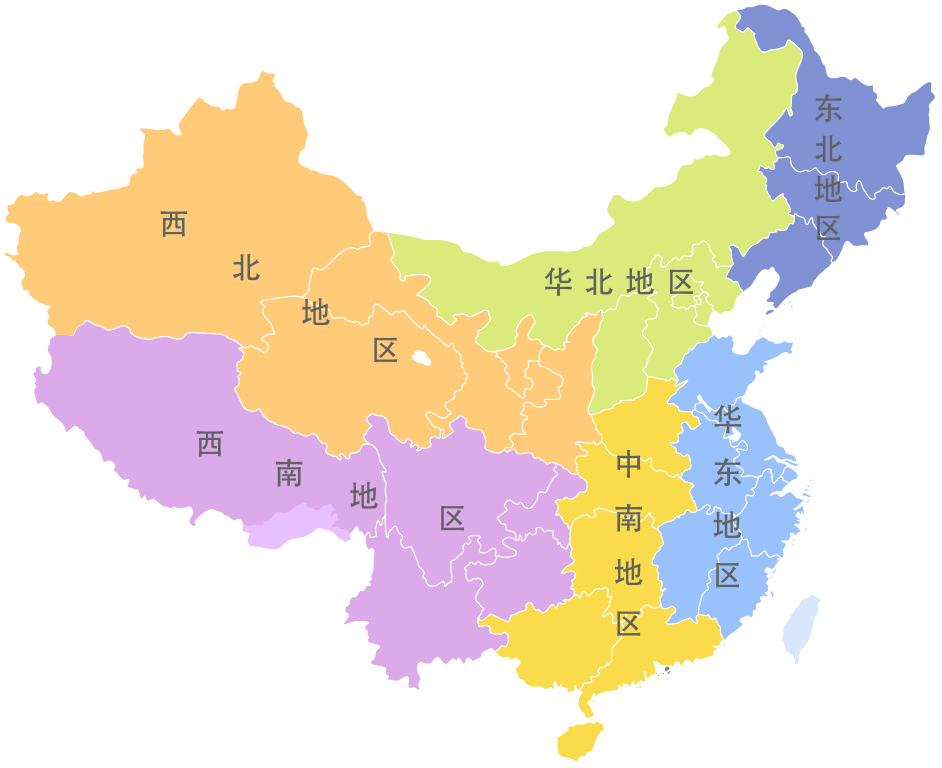

Traveling across China can be a linguistic adventure, as the country is home to a Babel’s Tower of unique dialects, each with its own distinct charm. From bustling cities and towns to quaint villages, you’ll find that Chinese dialects vary drastically from one locale to another. In fact, there are so many dialects across China – literally hundreds of them – that it’s hard to keep track of them all! Luckily, linguists have simplified things by grouping these dialects into seven main categories.

The Seven Main Dialects of China (or is that Ten?)

When it comes to the most widely spoken Chinese dialect, Mandarin Chinese is the clear winner, with over 70% of the Chinese population conversing in it. Originating in the north of China, Mandarin’s influence has now spread to all corners of the country. However Mandarin is not a one-size-fits-all language – it has several sub-dialects that vary greatly. Take Beijing Mandarin, for instance. Its unique pronunciation and vocabulary make it distinct from, say, the southwestern variation to the point where it is hard for the two groups of speakers to understand each other.

Moving down the list, the second most popular Chinese dialect is Cantonese, also known as Yue. This dialect is spoken in the southern regions of China, specifically Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau. It has become a popular dialect thanks to the persuasive influence of Hong Kong movies, television, and pop music (Cantopop). Cantonese is the only one of the major Chinese dialects that is also an official language, though this status is only recognized in Hong Kong and Macau, not in Guangdong itself.

Wu Chinese is spoken in and around China’s largest city, the bustling metropolis of Shanghai. It is also known as Shanghainese, and an estimated 75 million people speak it, rivalling Cantonese in number of speakers. If you head just south of Shanghai, you’ll find yourself in the province of Fujian, where the Min dialect reigns supreme. Through immigration, the Min dialect has spread to parts of Southeast Asia (where it is sometimes known as Hokkien) and also parts of Taiwan. Like Mandarin, Min has several recognised sub-dialects, so inland Min speakers find it difficult to understand coastal Min speakers, and Min speakers from Fujian struggle to understand the Min dialect spoken on Hainan.

Then there is Hakka, spoken by the Hakka ethnic group who can be found in areas of south China. Like the Min dialect, Hakka has been spread by the Chinese diaspora to parts of Taiwan and Southeast Asia. The Gan dialect, which has some similarities with Hakka, is spoken mainly in the province of Jiangxi. The seventh major dialect group is Xiang, which is spoken in the provinces of Hunan and Hubei.

Despite their vastly different spoken forms, all these dialects use the same Chinese writing system (except in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, where they write with traditional characters instead of simplified ones).

For several decades, the classification of Chinese into Seven Dialects was widely accepted. However, more recently linguists, particularly Chinese linguists, have extended the classification by an additional three dialects to better reflect the diverse linguistic landscape of China. The three additions are Jin, the dialect spoken in the Shanxi province; Huizhou, spoken in parts of Anhui province; and Pinghua, a hybrid of Xiang and Cantonese dialects spoken in Guangxi.

Interestingly, if you look at a Chinese dialects map, it is immediately noticeable that there is more diversity of dialects in the south-east. This is probably because for much of China’s history, this region was more isolated from the rest of the country. The southern region was a hinterland for the Chinese governments based in the north and central regions, and geographical features such as mountains and jungles added to the south’s isolation.

Is Sichuanese a Dialect?

The dialects spoken in Sichuan, also known as Sichuanese, are more closely related to Mandarin than they are to the dialects spoken in the south and south-east of China. Linguists usually classify Sichuanese as a sub-dialect within the Mandarin family of languages. However, don’t let that fool you into thinking it’s easy to understand for Mandarin speakers. For example, the popular Chinese movie from a few years back, Let the Bullets Fly (让子弹飞), which was set in Sichuan, had to be released in two versions. There was the Sichuanese version and also a Mandarin version to ensure non-Sichuanese viewers could follow the plot – even though a lot of the word-play humour was lost in translation.

Non-Chinese Languages of China

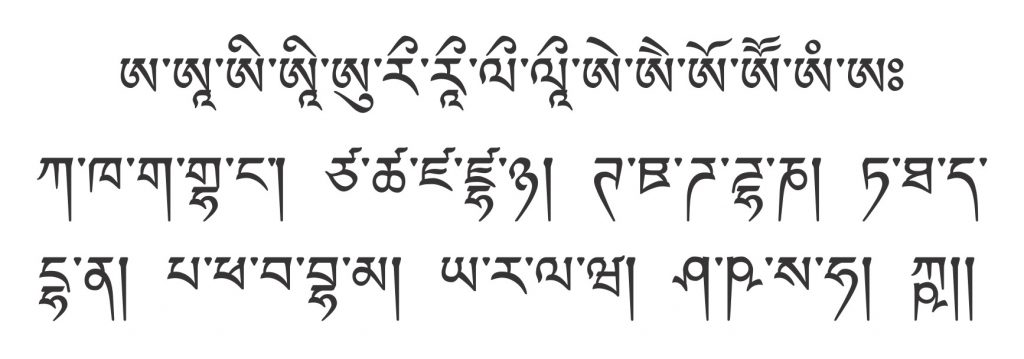

The above dialects refer to languages or dialects that belong to the Chinese or Sinitic language family. However, there are other major languages spoken by the main ethnic groups of China. Tibet has its own dialects, with the Standard Tibetan that is spoken in Lhasa the most widely used. (It is also a co-official language, along with Mandarin, in the region.) Not only is spoken Tibetan very different from Mandarin and other Chinese languages, but its writing system more closely resembles Indian scripts than Chinese characters.

If you venture to Xinjiang, you’ll find Uyghur as the official language alongside Mandarin. Uyghur belongs to the Turkic group of languages and has an Arabic-based script. It has an estimated 11 million speakers, including Uyghur communities outside China, in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and beyond.

Another of China’s official languages is Mongolian, spoken in the Inner Mongolia region. In fact, there are more Mongolian speakers in Inner Mongolia than there are in the whole nation of Mongolia. Mongolian has its own script; in Mongolia, the Russian Cyrillic script is also used, but not in Inner Mongolia.

There are a further six official languages in China. Zhuang is spoken in the south-western region of Guangxi and neighbouring areas and belongs to the same language family as Thai. Korean is one of the official languages of the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture bordering North Korea. Kazakh is an official language in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture on the western border with Kazakhstan. Nuosu (known in Chinese as Yi) is a dialect spoken mainly in Yunnan in China’s south-west, but also in Sichuan to the north and parts of Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand across the border. Finally, we have English and Portuguese, which are official languages in Hong Kong and Macau respectively.

Adding to China’s status as a linguistic treasure trove, there are even more non-official languages spoken in China than are listed here. However, many of these others have only a small number of speakers, or are rarely spoken and considered endangered, such as Manchus.

Which is the Easiest Chinese Dialect to Learn?

Looking to learn a Chinese dialect but wondering which one is the easiest? Well, while Mandarin is still a challenging language to tackle, it’s arguably the easiest of the main Chinese dialects. One reason for this is the abundance of Mandarin learning resources available, making it easier to find study materials and connect with other learners. (Although there are a growing number of Cantonese resources now available to help you learn).

As many Chinese learners struggle with tones, Mandarin might offer an advantage there too, because it has “only” four tones to learn. Cantonese has six tones (or nine, if you ask proud Cantonese speakers who boast about their language being the hardest in the world), and some Min dialects have a similarly high number.

Mandarin is known as having relatively simple grammar, and that’s generally the case with the other Chinese dialects. That being said, the Wu dialect has a more complicated system for using pronouns, while Cantonese has a lot more verb suffixes than Mandarin, and sometimes puts its adjectives after nouns.

If you’re open to exploring other languages spoken in China, Uyghur could be an option. As a Turkic language, it may be slightly easier for learners whose mother tongue is an Indo-European language. However, most Uyghur writing uses an Arabic-related script which can pose a challenge for those of us not familiar with it.

How Do Chinese Dialects Vary?

One of the biggest differences between the various Chinese dialects is in pronunciation. Some dialects have sounds that don’t appear in other dialects, such as the /v/ sound you hear in Shanghainese but not in Mandarin.

Another big difference, and also the source of much humour when people with different dialects get together, is in the vocabulary. There’s the story of the woman from Ningxia who met a Mandarin-speaking mother with her little daughter, and exclaimed “这娃娃真憨!”. She meant to say, “This child is so cute”, but to the Mandarin speaker, it sounded like, “This doll is really stupid”!

There are also some small grammatical differences between different dialects, such as word order and the use of measure words.

To get a better sense of the diversity among Chinese dialects, consider how different regions say the simple greeting of “Hello.”

你好 – Hello

Mandarin: nǐ hǎo

Cantonese: nei hou

Shanghainese: nong ho

Min: li ho

Xiang: li haw

Hakka: ngi ho

Gan: ng hao

Sichuan dialect: lee hao

How to Learn Chinese Dialects

Learning a new language can be an exciting and fulfilling experience, but if you’re looking to expand your linguistic horizons to include Chinese dialects, are there resources out there to help you get started? Well, when it comes to Mandarin, there is no shortage of learning materials, including of course The Chairman’s Bao. The Chairman’s Bao blog also has a wealth of articles with suggested resources, for example:

The Best YouTube Channels to Learn Chinese

10 of the Best Chinese Graded Readers and Where to Find Them

Best Chinese Vloggers on YouTube and BiliBili to Learn Advanced Mandarin

10 Best Resources to Learn Chinese Through News

Best Apps to Learn Chinese – an Honest Review

But what about the other dialects? For Cantonese learners, there are plenty of resources on the web, and the website Cantolounge has an excellent guide for people starting out in the language. Reddit has a r/cantonese subreddit that also provided comprehensive resources.

However, things get trickier when you start delving into less widely spoken dialects like Wu. Still, if you’re interested in learning this dialect, there are options out there, including a book called Shanghai Dialect for Foreigners that you may be able to pick up on Amazon. Some of the Chinese-language schools in Shanghai offer Shanghainese courses too, like LTL Mandarin School (which also has online classes). There are also some YouTube channels promoting Wu language, and regional TV stations that show Wu language programs. The Mango language app also offers Shanghainese, so that might be worth investigating.

Incidentally, if you already have a reasonably good Mandarin knowledge, it’s much easier to find resources to learn dialects, like textbooks that are in Chinese. This has the double benefit of not only learning a new dialect but improving your Chinese at the same time.

For those interested in non-Sinitic languages spoken in China, resources do exist, though they may not be as plentiful as those for Mandarin and Cantonese. Uyghur, for example, has some textbooks for beginner learners, and the FarWestChina blog has useful tips on what resources to use. The Uighur Collective also has a list of language resources to check out.

For Tibetan, there is a Colloquial Tibetan textbook in Routledge’s popular Colloquial Languages series which could serve as a good starting point. Several Tibetan language schools offer online courses – just be aware that some of them are teaching Classical Tibetan. Classical Tibetan is useful if you are learning Tibetan to read and recite religious texts, not so useful if you want to order in a restaurant or chat with locals at the market.

Mongolian is regarded as an especially tricky language to learn, especially pronunciation-wise, but if you are up for the challenge, then a good starting point would be the Learn Mongolian website. If you like learning by watching and listening, the YouTube channel Mongolian Language by the Nomiin Ger School is a great resource.

Ultimately, while it may take a bit more effort to find resources for learning Chinese dialects beyond Mandarin and Cantonese, the rewards of mastering these fascinating and unique languages are well worth the extra effort. Learning any Chinese dialect requires time, persistence, and dedication. But by taking advantage of available resources, you can set yourself up for success on this rewarding linguistic journey.

Author

Nick Dennis

Nick is an English teacher who has taught English as a Foreign Language in China, Italy and France. He has a Bachelor of Arts (Modern Languages), majoring in French, from the University of New South Wales. He loves travel, reading and football and, of course, learning languages. Four years ago, Nick and his wife co-founded an online English language school targeted at the Chinese market (since sold to Chinese investors). He has also ghost-written the autobiography of a well-known Australian horse trainer.